|

CULPRITS

Why frogs are vanishing

Before we

look into the reasons why, should we even care that frogs are vanishing?

o If we humans are responsible, we have a moral obligation to prevent

amphibian disappearances.

o Frogs may directly benefit humans. Australia’s gastric-brooding

frog, now extinct, had an enzyme-suppression mechanism that might

have helped people with gastric ulcers.

o Frogs eat disease-carrying insects.

o Frogs are critical links between predators and the bottom of

the food chain (algae, plants, detritus, and such). Frogs feed on many

organisms, and many organisms feed on them. Remove the frogs, and important

links are knocked out of the food chain.

o Frogs are important indicators of environmental health. Because

most frogs spend their early days in water and their adult life on land,

changes in both worlds may affect them.

Frog numbers are dropping in at least 140 countries. Biologists

have identified a number of reasons but suspect that a combination of

factors may be responsible.

James

P. Blair |

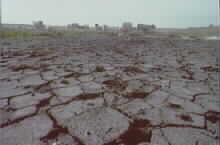

LOSS

OF HABITAT

The

number one cause of amphibian decline is habitat loss, and we humans

are to blame. By cutting down forests, damming rivers, and draining

marshes to build houses and shopping centers, we ravage landscapes

around the world.

Evidence: Most amphibians feed and breed in wetlands, so

loss of wetlands equals loss of amphibians. In the past half-century

the lower 48 states have lost more than half of their estimated

original wetlands.

Evidence: Urban development in southern California has gobbled

up 75 percent of the range of the endangered arroyo toad (Bufo

microscaphus californicus). Now the toad must compete with weekend

gold miners, fishermen, campers, and off-road fanatics for use of

its few remaining streams.

Evidence: In the United Kingdom, where many breeding ponds

have been filled in (as many as 80 percent in some areas), all six

native amphibian species have suffered dramatic population declines.

|

Erik

Enderson |

DISEASE

Amphibian diseases may be carried from continent

to continent by aquarium fish and exotic animals sold as pets. Disease

may also spread to frog populations on people’s boots or by

birds, insects, and livestock. Before tadpoles are moved from one

area to another to reestablish frog populations, biologists give

the youngsters a clean bill of health to prevent the spread of disease.

Evidence: A deadly virus is the likely culprit in several

recent die-offs of frogs, including spring peepers at Acadia National

Park in Maine, wood frog tadpoles in Massachusetts, mink frogs in

Minnesota, wood frogs and bullfrogs in North Carolina, and numerous

frogs at the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in Tennessee.

Evidence: Several species, such as Costa Rica’s golden

toad, may have disappeared because of chytrid (KIH-trid) fungus

(see photo). This infectious fungus spreads in water and can wipe

out entire populations or species even from pristine habitats. The

frogs most affected live in streams in mid- to high-elevation rain

forests. Climate change may also play a role.

Evidence: Scientists have detected chytrid fungus on almost

a hundred species of amphibians on six continents. More than 40

of those species are in Australia. Chytrid fungi are common in nature,

but this is the first one known to have attacked vertebrates.

Evidence: Most studies of amphibian disease are done in a

lab or on dead specimens. When Don Nichols, a pathologist at the

National Zoological Park in Washington, D.C., put antifungal medication

on captive frogs infected with chytrid fungus, the frogs recovered.

This method is being used to treat infected frogs in other zoos

and private collections.

|

|

Eric

L. Williams

|

CLIMATE

CHANGE

Amphibians have vanished even from wilderness areas.

As Earth’s ozone layer thins, increased ultraviolet radiation

may undermine the hatching success of the eggs of certain amphibians.

(Most amphibian eggs have a gelatinous coating but no protective

shell.) UV radiation can also alter the DNA in frogs’ cells

and suppress immune responses. At risk: Frogs that live at cooler,

higher elevations and extreme latitudes, where the ozone layer is

thinner but where amphibians must bask in the sunlight to regulate

body temperature.

Evidence: Increased exposure to ultraviolet radiation may

damage the eggs of the Cascade frog (Rana cascadae), which

lays its eggs in shallow water in high mountain meadows.

Evidence: Global warming may have caused the erratic weather

that ruined the breeding efforts of the golden toad in Costa Rica’s

cloud forest. In 1986-87 warm, dry weather dried up the pools before

the toads’ larvae had matured. Of a potential 30,000 toads,

only 29 survived. The drought may have caused the toads and other

amphibians to concentrate at the remaining pools, which facilitated

the transmission of disease and resulting death from the chytrid

fungus.

Evidence: Eggs and tadpoles need moisture to develop. In

southern California the endangered arroyo toad (Bufo microscaphus

californicus) lays its eggs in shallow pools created by spring

rains. During dry periods the toad can’t reproduce.

Evidence: In times of drought, frogs can become more susceptible

to disease or even dry up and die. When drought threatened a colony

of Chiricahua leopard frogs (Rana chiricahuensis) in southeastern

Arizona, a conservation-minded rancher trucked in a thousand gallons

of water a week for two years.

|

James

P. Blair |

POLLUTION

Since frogs breathe at least partly through their

thin, porous skin, they’re very susceptible to toxins. Industrial

pollution may be wiping out local populations. In farm areas, herbicides

and pesticides run off into the ponds, watering tanks, and irrigation

canals where frogs live and breed. Some herbicides interfere with

respiration, and certain pesticides and their by-products produce

severe limb deformities that prevent frogs from fleeing predators.

Evidence: Pesticides drifting up from farmland may be killing

amphibians in California’s Sierra Nevada and other wilderness

areas.

Evidence: Acid rain from air pollution can turn lakes, streams,

and wetlands into death traps. In Canada, Europe, and the northeastern

United States, acid rain has damaged forests and polluted soil and

water, making some areas unlivable for frogs.

|

|

Cecil

Schwalbe

|

INTRODUCED

AQUATIC PREDATORS

When sport and bait fish, crawfish, and bullfrogs

(Rana catesbeiana) invade lakes and wetlands where they’ve

never lived, these predators often devour native frogs and their

prey. Humans introduce most aquatic predators for sport and food,

while others escape from captivity or sneak in as stowaways on potted

plants.

Evidence: Introduced trout have nearly wiped out the mountain

yellow-legged frog (Rana muscosa) in California’s Sierra

Nevada.

Evidence: In southeastern Arizona sport fish and the bullfrog,

introduced from the eastern United States a century ago, have nearly

eaten the Chiricahua leopard frog (Rana chiricahuensis) out

of its native waters. The aggressive, fast-growing bullfrog devours

anything it can fit in its mouth: tarantulas, native frogs, rattlesnakes,

bats (see photo), songbirds, and many other creatures. A bullfrog

can lay as many as 20,000 eggs per clutch.

|

|

OVERHARVESTING

People harvest frogs for food as well as for hides,

pets, and research. Some states and countries have banned the commercial

harvesting of frogs for dissection in biology classes. Frog-friendly

alternatives include videotapes, 3-D anatomical models, and interactive

CD-ROMs.

Evidence: In the late 1800s the massive collecting of California

red-legged frogs (Rana aurora draytonii) for food depleted

local populations, which led to the introduction of bullfrogs (Rana

catesbeiana).

Evidence: Between 1981 and 1984 Americans devoured more than

6.5 million pounds of frog legs a year, which led to the death of

some 26 million frogs annually. Ninety percent came from India and

Bangladesh, which banned exports after frog declines led to growing

hordes of mosquitoes, malaria, and increased use of pesticides.

Now Indonesia supplies most of the frogs for restaurants.

|

|